I am on the phone with a potential client. We’ll call him Mr. L. “What we’re using,” Mr. L tells me, “is a long-tail content strategy.”

“How’s it working?” I ask.

“It’s okay,” he admits. “But we need help creating 1,000 content pieces a month.”

“Our price for a great blog post is $49, so that’s $49,000,” I respond. “Do you have a monthly budget of $49,000?”

“What? No! My budget is $2,500.”

“So why don’t we put that budget toward content that will make a difference, content that more of your customers are searching? You do business insurance, right?”

“Yes.”

“The long-tail strategy is to write content for tiny niche topics like ‘How to Find Business Insurance for Seniors in Peoria’ or ‘How to Get Cheap Business Insurance for Alpaca Grooming Clinics.'”

He laughs.

“Why not spend our energy creating useful content that applies to everyone looking for business insurance?”

“Because that stuff has been written a million times!”

“Why not write it again, but better?”

He pauses. “That’s not a long tail strategy.”

“Exactly.”

The Long Tail Explained

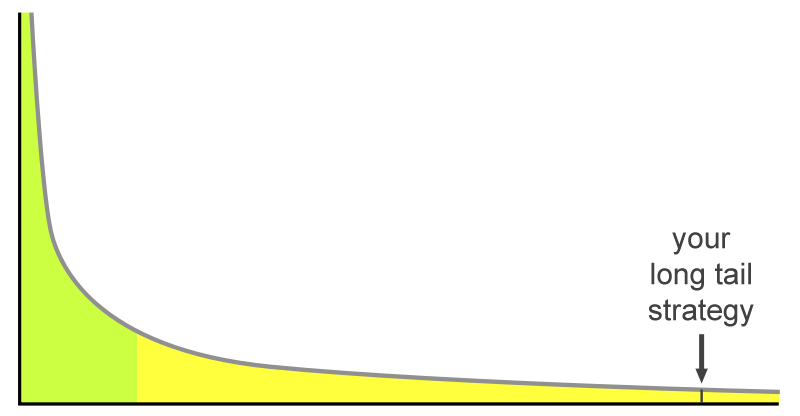

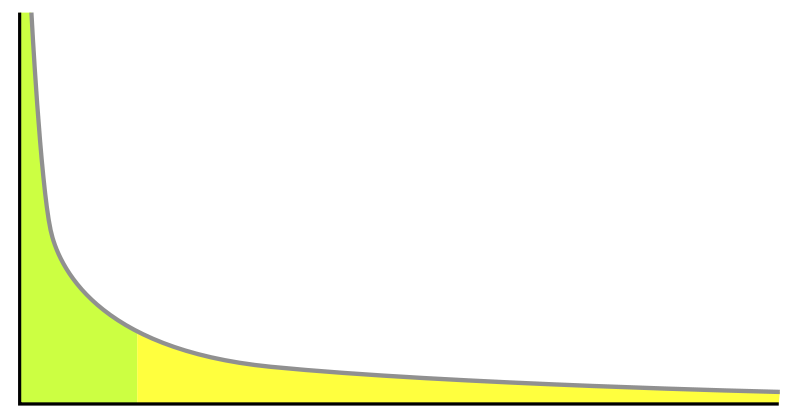

The “long tail” has been around for years in statistics, describing the long distribution of values that fall outside the most popular “head” values. It’s easiest to visualize with a graph:

The large green area on the left is the “head”; the long yellow area on the right is the “tail.”

The term was popularized in a 2004 article by Chris Anderson in Wired magazine. In Anderson’s definition, the “long tail” is the collection of niche customers that can be served just as profitably as the most common customers, given certain conditions.

For example, Amazon has achieved world dominance by selling a much wider variety of books than were ever available in your local bookstore. The “head” books would be Harry Potter and Fifty Shades of Grey, while the “tail” would be millions of books like The Ultimate Guide to Crochet 1975. While bestsellers still make up the majority of sales, the obscure and hard-to-find books comprise about a third of total sales.

Think about Netflix, as opposed to a movie theater. The theater has limited space, so it can only show the newest, most popular movies (the “head”), while Netflix has virtually unlimited space, so it can offer nearly every movie made (the “tail”).

We can offer many examples of companies that make the long tail work as a successful business strategy. But a “long tail” strategy is misused by most companies, which causes them to waste vast amounts of time and money.

I will explain why, using examples from content marketing, since that’s our business at Media Shower.

The Illogical Reasoning

What Mr. L is saying, in essence, is, “The most popular topics — the ‘head’ topics — have already been covered by my competitors. We can’t succeed, so let’s go after the ‘long tail.’ Even though there are only twelve alpaca grooming clinics in the United States, we can own them.”

This reasoning is a misunderstanding of the long tail principle, which rests on two factors:

1) The cost of servicing the long tail must be close to zero. In the case of Amazon and Netflix, they have such economies of scale that warehousing and distributing each additional book or movie approaches zero. Or take a digital company like Google: thanks to their massive server farms, servicing long tail customers is practically free.

This is not the case with most marketing endeavors, and certainly not content marketing. It costs money to create good content. As I explained to our potential client, a long tail strategy would be very expensive, and those alpaca grooming clinics would need to be pretty big customers.

Long-tail content strategies have been pursued by other companies, churning out massive volumes of low-quality content and paying writers next to nothing. You know the sites I’m talking about, because they once dominated the search results. That kind of dominance never lasts; the search engines (and customers) demand good content.

2) You need to own the entire long tail, not a slice. In my experience, most people who talk about the “long tail” are really thinking of “a slice of the long tail,” not “the entire long tail.” What they are really talking about is “a few niche customers”:

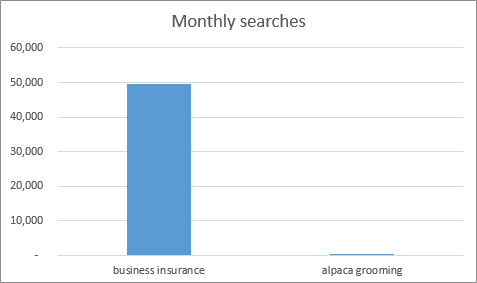

If you take a moment to do the math, you’ll see this makes no sense. Here, for example, are the number of Google searches performed monthly for “business insurance” vs. the number of searches for “alpaca grooming”.

You could spend hundreds or thousands of dollars creating the best content for this long tail search, and in the end, you’ll reach a maximum of 30 potential customers per month. The marketer who goes after “business insurance” (the head search), on the other hand, will get in front of 50,000 customers.

Now multiply this strategy across hundreds and thousands of “long tail” topics, and you’ll see why the math doesn’t work.

The tail is the best part of the lobster, but only if you eat THE ENTIRE TAIL. Not a slice of tail one micron wide.

Long Tail = Long Shot

If I had to estimate, the percentage of people who succeed with a long tail strategy is .000001%. That’s a math joke. The easiest way to describe the long tail strategy is with some analogies.

“We can’t reach CEOs, but we can reach red-haired CEOs named Fred who live in Peoria.”

“I can’t sell this product to mothers, but I can sell to first-time mothers over 65 with one knee.”

“Our soccer team can’t win, unless we play against Albanian children.”

“I can’t make money as a stockbroker, but I can stand outside the stockbroker offices and ask for tips.”

The long tail, in most cases, is really about a lack of confidence. “We can’t succeed, we can’t compete, it’s too difficult.” It’s a fancy version of the excuse we often hear from small- to medium-sized businesses: “We’re too small.” This is a self-reinforcing loop: when you think small, you stay small.

Be fearless! Have courage. There is always a way to win.

One of my favorite books to illustrate this point is Moneyball. The movie is great, but the book is even better. It illustrates the point that you can succeed even if you are underresourced and underprivileged. Even in an industry as mature as professional baseball, there are still winning strategies — new ways of approaching the game — that will let the little guys win.

I had a college roommate who was going for his Ph.D. at MIT. We were discussing his dissertation and he said, “The problem is, all the good ideas have already been taken.” This is crazy, of course. There are always natural laws waiting to be discovered.

Similarly, no industry is completely mature. There is always a hidden doorway somewhere that will allow you to sneak by your larger, slower competitors. There is still a universe of great content waiting to be created.

Forget the long tail. Take on the body. That’s where the money is.

Sir John Hargrave is the CEO of Media Shower and author of Mind Hacking, available in 2016 from Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books. This post is free to distribute under Creative Commons 4.0: if you like it, share it.